Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture Catherine De Almeida remembers picking up trash on the playground, seeing people throw trash out their car window, and noticing trash flying around while she played outside as a child. The presence of litter in landscapes upset her so much that she would spend her elementary school recesses picking up trash.

When she got into the field of architecture, De Almeida found herself drawn to how things could be flexible and take on multiple identities – in other words, do more than one thing for more than one person. Her first exploration of this was during her architectural education when she did a project on urban housing. As an architecture student in New York City, De Almeida thought a lot about small spaces and how walls are spaces that can serve more purposes than we might typically think. She took this way of thinking further in her furniture design class, taking interest in transformational furniture — furniture that can change shape, size, or function.

Going on to graduate school for landscape architecture, De Almeida continued this interest and applied it to materials: looking at materials that are made from recycled content, can biodegrade, have an extended life, or no end of life. Her early studies informed the way she continues to think about design and in looking for different ways to engage with our waste “problem”. From her perspective, waste itself is not the problem, it is relationships to it – what we produce, how we manage and perceive it – that is the issue, causing current water, food, climate, and ecological crises.

De Almeida asks important questions: why is waste created; why is it removed so quickly; and why is it easier and cheaper to buy something new rather than repair it?

De Almeida writes in her forthcoming article, Sharing Waste: From Undesirable Conditions to Collective Opportunities, that “[our] shared cultural [mis]perceptions of waste have become embedded in certain design approaches, driving unconscious aesthetic decisions to fix and hide waste rather than engage with it.”

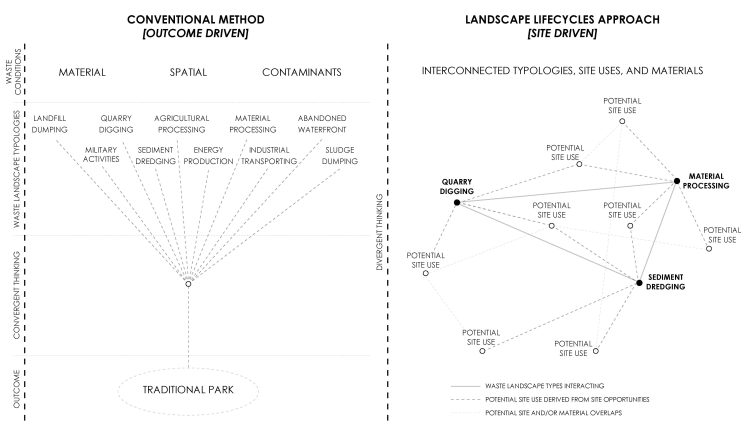

De Almeida refers to her design-research framework as “landscape lifecycles.” Her framework applies a “material lifecycles” lens to the inventory, analysis, and design of the places where we store our waste. De Almeida sees waste as the common denominator in everything and every place, and because of this, is also able to see and communicate about the interrelatedness of things, places, and activities that are typically seen as being separate. She uses this framework to investigate the performance, visibility, citizenships, emotions, and injustices of waste materials and landscapes that are leftover from socio-economic, urban, and industrial processes. De Almeida has found that this approach broadens typical definitions of inputs and outputs in lifecycle assessments to include the human, more-than-human, and perceptual and spatial dimensions of waste.

De Almeida’s framework hints at what is lacking in the current ways of dealing with waste: unity, integration, and collaboration.

Her ideas are inspired by landscapes of reuse that are often accidental or novel and constantly evolving. Such landscapes have the potential for multiple uses, activities, and enterprises by sharing or exchanging waste materials, rather than allowing them to fall out of circulation like excess food scraped into the sink. One example De Almeida has written about is the Blue Lagoon, in Iceland. It is a high-end spa whose main feature is a lagoon created by geothermal waste effluent from an adjacent geothermal combined-heat-and-power plant. The effluent contains a novel microbial environment that has health benefits for humans. After the lagoon was created and its accidental benefits realized, similar efforts have spawned in various industries nearby, boasting “benefits” from carbon sequestration to fish processing to hiking trails. The overall system is now known as the Resource Park.

One of the ways in which current waste systems in the US are flawed, De Almeida argues, is that they don’t account for key differences among different kinds of waste: blending all forms of toxic and non-toxic wastes into a single stream. Additionally, overconsumption creates large amounts of waste, which is quickly removed and often shipped somewhere else.

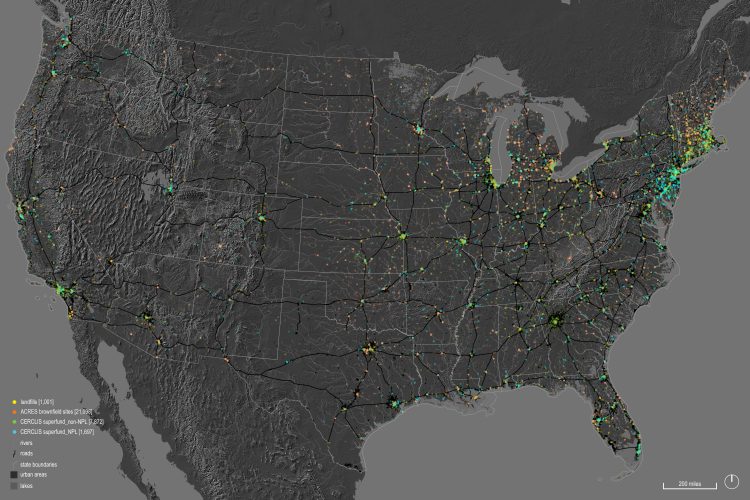

Among the many flaws in our waste system, one thing we know for sure: our single-stream model causes inequities for many communities. Most waste produced in the U.S. goes to landfills, and landfills impact the water, soil, and air quality in the ecosystems and communities they occupy.

Moving waste from place to place creates even more waste. As trucks transport waste to landfills, communities along the way are impacted. As waste travels through cities and towns to get to the landfill, the smell, unintended debris, and diesel emissions from garbage trucks add another level of inequitable impact on communities, often lower-income communities and communities of color.

De Almeida believes that by asking better questions, right from the beginning, we can shift to a system built on cooperation, coordination, and collaboration.

She asks, “how do we connect people, activities, and working processes so that waste being produced in one place can be used for another purpose?” This concept has been popularized by the term circular economy. A circular economy is “based on the principles of designing out waste and pollution, keeping products and materials in use, and regenerating natural systems.”

“It is astonishing how waste is handled. To address it in the short term, it is transported to far away places, sometimes internationally, affecting communities along a global chain of waste removal and storage. In current climate crises, it is irresponsible to not consider the longer-term consequences of materials forever lost out of circulation, and the unequal impacts of who has to bear the brunt of such decisions” – Catherine De Almeida

De Almeida’s research also scales from hyperlocal environmental impacts to international waters, where she points out another scale of injustices occurs. “The global scale at which waste materials move around is astonishing,” she shares. The book, “Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor,” by Rob Nixon, which De Almeida recommends, explains how the ways pollution is created and dealt with is a form of slow violence against the planet and communities who have no say and are forced to deal with others’ waste. Again, often poor and communities of color.

De Almeida encourages built environment scholars, practitioners, and students to think about their work on multiple levels, and the potential waste that is produced at every stage of a project. She is hesitant to say that she has “solutions”, but would rather frame it as an opportunity to rethink the way we design, and to focus on impact rather than a singular “solution.” De Almeida believes there are multiple ways to address these challenges. As she tells students, “our imaginations are our biggest limitations.”

“Designers have the capacity to design with waste instead of against it.”- Catherine De Almeida

By re-imagining waste through landscape lifecycles, De Almeida believes we can uncover new relationships among the diversity of waste conditions that intentionally make waste visible. Rather than avoiding their challenging conditions, waste landscapes must be embraced as opportunities for creating productive relationships with waste as a common ground…” – Catherine De Almeida, The Blue Lagoon: From Waste Commons To Landscape Commodity